Learn About O’odham and Piipaash Traditional Cultures

The O’odham and Piipaash of the Salt River are federally recognized as a single tribe because we have historically functioned as a single political entity when dealing with other tribes and groups of people. That remains true today, however, we are and always have been two distinct tribes in terms of culture and identity. Because we share the same environment and have maintained close social ties with one another, many aspects of our traditional material cultures (e.g. houses, clothing, food, etc.) are similar.

This page includes basic information about some of the most common inquiries regarding our traditional cultures. Additional cultural information is available on our Cultural Resources Department site.

Dwellings and Other Structures

From the early pit houses of prehistoric ancestors to adobe block homes and communal ramadas, the traditional dwellings of the Onk Akimel O’odham (Pima) and Xalychidom Piipaash (Maricopa) reflect a deep connection to the Sonoran Desert environment. These homes and utilitarian structures weren’t just shelters — they were expressions of ingenuity, adapted to climate, lifestyle, and cultural values. Learn how historic housing types like jacal and round houses evolved into structures still recognized in the Community today.

Prehistoric Houses

Our huhugam built and lived in houses of various styles throughout time. Their pit houses were somewhat similar to our historic round houses. Later they built walled-in compound structures and large multi-level adobe structures. Extensive information on these dwellings can be found at the Casa Grande Ruins National Monument, S’eḏav Va’aki (Formerly named Pueblo Grande Museum and Arizona Museum of Natural History websites, so we’ll focus on sharing information about our historic structures.

Round Houses

Historic O’odham and Piipaash houses were generally constructed using the same materials and methods. Prior to European influence, our houses were of the type that we now refer to as ‘round houses’. In O’odham, this type of dwelling is called an olas ki. In Piipaash, a dwelling of any style is simply called a va. The general shape and size of round houses approximated a dome about 20’ in diameter and just tall enough for one to stand upright. The framework of the round house was made of mesquite or cottonwood and willow. The thatching was commonly arrowweed, but any locally abundant material might be used. Dirt was placed on the roof and banked up the sides to keep out the rain. The floors of some houses were slightly excavated. Some variation in size and design existed but doorways were invariably located on the east side. Doorways were rather small, requiring one to crouch when entering. The construction of round houses began to decline in the late 1800s and essentially ceased by the 1930s. Today, round houses are built only for special functions and occasions.

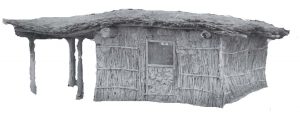

Jacal

The flat roofed and rectangular jacal-style houses (sometimes referred to as wattle and daub) were erected by early Hispanic settlers who may have adopted it from tribes in southern and central Mexico. Jacal houses were adopted by some O’odham and Piipaash as early as the 18th century and endured through the early 20th century. O’odham and Piipaash jacal-style houses used many of the same materials as the round houses that preceded them.

Adobe Block Houses

Native peoples in the Southwest have been using adobe for generations, but the Spanish introduced the wood form molded brick. Early on, the Spanish urged the O’odham and Piipaash to build more permanent structures and this admonishment was continued by the U.S. government. Such efforts were generally unsuccessful until the 1880s when the assigned Pima agent, Roscoe Wheeler, initiated an incentive program, offering a wagon and harness to tribal members who would build an adobe house as a permanent residence. Subsequently, adobe block homes became commonplace for many O’odham and Piipaash.

Sandwich Houses

Sandwich houses are a unique style of housing initiated in the 1920s. Milled lumber was used for the framework, frequently scrap lumber that was repurposed. The support posts were most often railroad ties. Horizontal slats of wood were attached on the inside and outside of the support posts. The space between the horizontal slats was packed with mud, creating an adobe insulation as thick as the railroad ties. The roofs of early homes were thatched and covered with dirt. Subsequently, pitched roofs were made using plywood and rolled roofing material. Sandwich houses often consisted of one large room, but they could and often were divided into separate sleeping, cooking and storage areas. The floors were dirt, maintained by sweeping and sprinkling them with water. This style of home was common through the 1970s. They became less common as tribal members began to build homes similar to the surrounding non-native population. Most tribal members today live in modern homes, but remnants of sandwich houses can still be found in the Community.

Ramada

Ramadas are shade structures that were built adjacent to, and sometimes attached to, every home throughout most of our history. Many daily activities took place under the shade of the ramada rather than inside the house. This structure is called a vato in O’odham and mathkyaaly in Piipaash. They are usually four-post structures (more posts can be used for a larger one) with a thatched roof of arrowweed or whatever abundant and serviceable material might be found locally. Traditional and contemporary style ramadas are still frequently used today for various purposes.

Kitchen/Windbreak

Circular windbreaks made from a framework of wooden posts, willow and arrowweed were constructed near some homes. This provided a wind break that facilitated cooking over an open fire. This structure is called uk’ṣa in O’odham and ’iish in Piipaash. Use of these structures faded with changing housing styles that accommodated indoor cooking.

Other Structures

Other traditional structures included storage sheds, menstrual/birthing houses, granary platforms and council houses. The latter was generally constructed using the same materials and methods of regular houses, only larger in size. Most villages had one of these structures where males would gather to smoke, discuss relevant issues and make decisions.

Subsistence Practices

For generations, agriculture, hunting, and wild harvesting sustained the O’odham and Piipaash people, who cultivated the land along the Salt and Gila rivers with precision and care. Traditional foods like tepary beans, mesquite, and squash remain symbols of resilience and identity. This section explores how ancient farming practices, native food plants, and desert-adapted methods continue to influence contemporary diets and food sovereignty efforts within the Salt River Pima-Maricopa Indian Community.

Agriculture

Our ancestors were skillful irrigation farmers who grew crops adapted to the extreme Sonoran Desert environment. Several varieties of corn, beans and squash were the staple foods grown; a diversity of supplemental foods was also grown seasonally. Cultivated foods made up nearly half of the native diet. Spaniards, Mexicans and Americans introduced new crops upon their arrival, some of which were immediately embraced by our people. Items such as wheat, melons, sugar cane, figs, and pomegranates became a commonplace. A variety of non-food native plants such as cotton, tobacco, devils claw and gourds were also cultivated. Every man, woman and child played a role in planting, tending and/or harvesting the family fields. Agriculture was a core and vital aspect of our traditional cultures, but it was severely affected as non-native settlers began to divert the river waters for their own uses.

Many historical events and federal government policies lead to the ultimate demise of traditional farming, and by the 1940s tribal members had largely abandoned farming because it became economically impracticable to sustain. The complexity of the allotment system made leasing land to commercial non-native farmers the most feasible option of securing income for survival. Today, about 12,000 acres of land in the SRPMIC are under cultivation but none of it is directly farmed by tribal members, with the exception of a few family gardens.

At present, the Cultural Resources Department maintains a small demonstration garden and seed bank to ensure the survival of native and traditional crops. Educational programming and support is available to encourage tribal members to maintain home gardens and revitalize an important part of our traditional cultures.

Wild Food Plants/Items

The Sonoran Desert provides a bountiful food supply if one has the knowledge and skills to make the most of it. The O’odham and Piipaash depended on wild food items such as mesquite beans, cholla buds, saguaro fruit, prickly pear, and a wide variety of wild seeds and greens.

These wild foods are nutritious and many of them have the additional benefit of regulating blood sugar levels. Over many generations, our bodies have adapted to exist harmoniously with the nourishment provided by our environment. Some tribal members still utilize these wild food items but most do not do so on a daily basis. Straying from a regular diet of native foods and active lifestyles has had negative health consequences, especially with regard to diabetes.

A resurgence of interest in native foods among younger tribal members is encouraging, however. The Cultural Resources Department regularly organizes wild food harvests and classes that teach how to prepare and cook those items in traditional and contemporary ways.

Hunting and Fishing

As river tribes, our ancestors formerly ate an abundance of fish. A variety of fishing methods was employed, the simplest of which was to dive in and catch them with bare hands. Unfortunately, only a small section of the Salt River still flows through our Community, and the native fish species are a distant memory.

Small game and fowl such as cottontail, jackrabbits, ground squirrel, quail, dove and turkey were hunted most frequently. Larger game such as deer, mountain sheep, antelope and javalina were also hunted, but not as frequently. Hunting was traditionally a male endeavor and the taking of life considered a serious affair. There are traditional guidelines that one must adhere to so as not to offend certain animals and cause sickness. First time hunters must always give away their first kill to older people.

Traditional hunting and fishing has not ceased, but it has declined due to cultural and environmental changes.

The gathering of insects can hardly be called hunting, but some insects such as caterpillars were formerly gathered and eaten in abundance when they were plentiful in the rainy season. Cicadas were also a common snack food when abundant in the summer. A few tribal members still roast and indulge on the occasional cicada for old time’s sake, but most of the younger tribal members probably couldn’t imagine doing such a thing today.

Contemporary Traditional Food

This sounds like an oxymoron but it’s an accurate description of foods that are not native, but have been consumed long enough that tribal members consider them traditional.

When traditional farming was disrupted by water diversion, the federal government compensated by providing rations of food such as highly processed white flour and lard. O’odham and Piipaash women found innovative ways to make the best of what they had to cook with. Tortillas (cemait / modiily) and frybread (wuamajda / chshaylytap) became commonplace. Over time they became considered traditional food items. Beef largely replaced wild game and fish. Mexican influences inspired dishes such as chili stew, burritos, and tamales that have a distinct O’odham-Piipaash flair. These contemporary traditional foods have evolved past mere survival foods and are quite delicious, but not nearly as healthy as our original native foods.

Clothing

O’odham and Piipaash clothing styles have changed over time. Also within any particular time frame, there has existed a certain amount of diversity in clothing style between individuals. In general, the O’odham and Piipaash wore little clothing prior to contact with non-natives. Living in the hot Sonoran Desert did not require excessive clothing.

The scant clothing worn by our people did not sit well with the non-native settlers, however, who saw things through a different cultural filter. The new comers urged O’odham and Piipaash women to cover their upper bodies and urged men to wear more than a breechcloth. As modern towns were established in our homeland, modesty laws were put in place, requiring our people to wear contemporary clothing that covered more of their bodies. Our people were not completely resistant to that suggestion. The new style of clothing was considered an interesting novelty item for some O’odham and Piipaash. For day-to-day activities, however, most preferred to wear their traditional garments.

There are stories about how communal clothing would be hidden in bushes at the edge of town, available for any O’odham and Piipaash who needed enter town to conduct business. Upon exiting, they would put the clothing back in the bushes for others to use. Today, most O’odham and Piipaash wear the same styles of clothing as the surrounding populations and traditional clothing is limited to special occasions.

Women’s Clothing

Prior to contact with non-native peoples, O’odham and Piipaash women wore clothing that covered only the lower part of their bodies. Early women’s skirts were often made from strips of processed willow bark that were tied to a belt. Another early type of skirt consisted of a blanket wrapped around the waist. In colder weather, these cotton blankets could be wrapped around the upper body as well.

After contact with the Spanish-Mexican and American populations, new styles of dress were eventually adopted by O’odham and Piipaash women. Most often this consisted of a peasant-style blouse with a skirt. Sometimes simple one-piece dresses were also worn.

O’odham and Piipaash women probably didn’t make their own contemporary dresses until they learned how to do so at Indian boarding schools and day schools in the late 1800s. After they learned how to sew their own dresses, they began to include stylistic design elements of their own cultures. Traditional basket, pottery and petroglyph designs became commonly incorporated features and still are today. For Piipaash women, the use of rick rack became commonly used as a representation of water. Some women began to design their dresses using specific colors to represent different meanings. Such color symbolism, however, is generally personal and not a universal norm.

Today, when we refer to traditional O’odham and Piipaash dresses, we are usually referring to that early peasant-style dress with O’odham-Piipaash design elements. The materials and design elements have become a more ornate over the years and each generation adds its own flair, but the same basic dress style has endured for over a century.

Men’s Clothing

Prior to contact with non-native peoples, O’odham and Piipaash men’s clothing consisted primarily of a breechcloth that hung down to just above the knees in front and to the lower leg in the back. Later, the breechcloth took on a more streamlined look with no material hanging from the front or the back. They too were encouraged by the non-native population to cover their bodies and adopt “civilized” clothes.

American government representatives sometimes presented suits as gifts to recognized tribal leader as symbols of their status. By the early 1900s, most men wore a wide variety of non-native style clothing.

At some point, “ribbon shirts” came into fashion for men. This was not distinctly an O’odham or Piipaash invention; rather it is a style adopted by many different tribes. There are a number of different stories by different tribes about the origin of the ribbon shirt, but for O’odham and Piipaash men, it is simply something adopted and worn for aesthetic purposes. Today, some ribbon shirts have distinct O’odham and Piipaash design elements and are usually worn for special occasions.

Footwear

In the old days, most O’odham and Piipaash went bare foot most of the time. Footwear was only worn when necessary (e.g. extreme terrain). When it was necessary, simple leather sandals did the trick. No moccasins of any kind were worn. Today, some tribes in Mexico compete in and win ultra-long distance marathons, running 100 plus miles wearing nothing on their feet or wearing only simple sandals such as we once did.

Other Adornment

O’odham-Piipaash men and women frequently adorned themselves with earrings, bracelets and necklaces made of shell and stone. Sea shells from the Gulf of California were especially prized. Formerly, it was common for men to adorn their hair with down feathers. The bravest men had pierced nose septums and wore feather bonnets. Most individuals were tattooed, the most common location being the face. Clay paints provided additional facial, hair and body adornment when the occasion called for it. When glass beads were introduced they also became prized adornments and were used to fashion new styles of jewelry.

Other Items of Manufacture

The artistry and functionality of handmade items — from woven baskets to clay pottery — showcase the innovation and storytelling of SRPMIC ancestors. These objects served everyday purposes and ceremonial roles, and continue to be powerful cultural markers. Discover the significance of tools like the calendar stick, and how traditional crafts still hold an important place in Community expression, heritage preservation, and intergenerational knowledge-sharing.

Basket Weaving

Previously, baskets were utilitarian items, used primarily for food preparation, and basket weaving was formerly a skill practiced only by women. O’odham and Piipaash women made coil baskets that were identical in material and design.

This coiling style uses split cattail stalks as a foundation material. Lengths of split willow shoots and devil’s claw are used to weave the intricate designs. The process of gathering and processing the materials, then fabricating them into tightly woven, intricate designs is extremely time consuming and requires tremendous skill.

When commercially manufactured bowls and dishes began to replace baskets in the food preparation process, basket weavers found a new reason to weave. Non-natives appreciated these baskets for their artistic value and were willing to purchase them. Women then found a new way to contribute to the household income.

It was at this point that new forms and designs also emerged, and while basket weaving had always been an art form, the artistic aspect of it became a primary consideration. O’odham and Piipaash baskets that sold for just a few cents in the early 1900s now sell for thousands of dollars and are considered among some of the best in the Indian arts and crafts market.

Although this particular style of basket weaving was practiced by women of both tribes, it originated among the O’odham, and it was primarily O’odham women who carried the tradition to present. Hence, the style is known as “Pima basketry”.

Today, there are just a handful of basket weavers who maintain this traditional art. Classes are being taught and the knowledge is still generally limited to women. However, there are a few O’odham men here and elsewhere who have learned to weave as well. Storage baskets, sleeping mats and other items were also formerly made using other styles of weaving, but these forms have not survived locally.

Pottery Making

Previously, ceramic vessels were utilitarian items, used primarily for food preparation, water vessels and food storage. Different ceramic forms, each having a distinct name, were made with a specific function in mind. Cooking vessels were undecorated, but items such as cups and bowls were often polished and painted with beautiful designs.

Piipaash and O’odham women made pottery using the paddle and anvil method. When commercially manufactured bowls and dishes began to replace the functionality of traditional ceramics, pottery makers found a new reason to continue their art form. Non-natives appreciated the decorative pottery for their artistic value and were willing to purchase them.

In the 1930s regional and local museums along with concerned supporters worked with Piipaash potters to establish the Maricopa Pottery Cooperative. Their goal was to build a retail market by establishing a cooperative relationship with brokers, dealers, and buyers of their work.

At this point in time, new forms and designs emerged. While pottery making had always been an art form, the artistic aspect of it became a primary consideration. The main ceramic style that found favor in the market is commonly referred to as “Maricopa pottery”. This style is defined by the use of a red and/or white clay slip that is burnished until it looks almost as if a glaze has been applied and finished with painted designs using black mesquite sap.

Although women of both tribes probably made this style of pottery, it was primarily Piipaash women who carried the tradition to present. Today, there are just a handful of potters who maintain this traditional art. Interestingly, in the Salt River Community, the most prolific potters are currently men. These modern potters are experimenting with new styles but are firmly committed to using traditional materials and methods. Classes are being taught with the hope that this art form will continue well into the future.

Calendar Stick

Like many other cultures, the O’odham and Piipaash feel it important to remember and transmit knowledge of significant historic events to younger generations. Formerly, this knowledge was primarily transmitted by way of oral tradition. Within both tribes, however, individuals have also maintained Calendar Sticks. Calendar sticks are often made from lengths of saguaro cactus rib, but other types of wood are also used. On the face of the calendar stick, lines are carved along its circumference to represent the passing of a year. Between those lines, symbols are carved to represent the most significant events occurring within that time frame. These symbols were not part of a universally recognized writing system; rather, they were simply mnemonic representations that helped the keeper to remember events. A few individuals still practice the tradition of recording events in this manner today. Along the Community’s business corridor, the branding concept of Talking Stick is derived from the traditional O’odham and Piipaash Calendar Sticks.

Music

Music is more than sound — it’s history, language, and tradition passed through generations. Traditional songs and instruments of the O’odham and Piipaash communities have long played a central role in ceremony, celebration, and storytelling. Today, styles like waila (also known as “chicken scratch”) blend heritage and modern rhythms, continuing to bring people together across generations. Explore the evolution and enduring significance of Salt River’s musical traditions.

Traditional Music

Although there are powwows held in the SRPMIC today, and some of our tribal members actively participate in them, this is a contemporary practice. The Plains styles of powwow singing and dancing are not native to this area. Traditional O’odham and Piipaash songs have a totally different form and sound.

Large skin drums were never used by the O’odham and Piipaash. Instead, large coil baskets that were overturned and struck with an arrowweed stick provided the accompaniment for many songs. Coil baskets are seldom used as drums today due to their rarity. At some point in the not too distant past, singers began to use cardboard boxes in place of baskets because they were readily available and they provided a similar sound. Cardboard boxes are still used today to the surprise of others who might mistakenly assume someone left the real drum at home. Another common accompanying instrument for our traditional songs is the gourd rattle. Less frequently used is a wood rasp.

O’odham and Piipaash songs are actually complex song series that, if sung in their entirety, can last from dusk to dawn. A particular song series may have dozens and up to hundreds of individual songs that follow a sequential order. These song series are not composed by any individual but are originally acquired through dreams. There are a number of different types of specialized dances, but the most common is the social round dance where the dancers grasp hands and form a circle, stepping to the beat of the song in a counterclockwise direction. The Piipaash also commonly sing songs that are shared among other related Yuman tribes where the most common form of dancing is with males and females facing one another in a line, dancing forward then back.

Valia (“Chicken Scratch”)

Another form of social dance music that has been around since the 1800s is commonly referred to as “chicken scratch”. This form of dance music is a hybrid of European polka and waltzes with a variety of Mexican influences and is usually played by bands wielding instruments such as the guitar, accordion, saxophone, drums and base. The style of dance accompanies the style of song, but the dance is always directed in a counterclockwise direction. The O’odham call this type of dancing Vaila (or Waila) borrowed from the Spanish word bailar. Although not of native origin, this style of music and dance is now considered a traditional form of music.